The alchemy of time and objects

Notes on purging, packing, & how objects connect us to our past selves

I’ve never been one for spring cleaning. I’ve been one for spring seed starts and garden planning, yes — but rarely do I have the urge to clean or go through my things to clear up space. That is, until now.

In what I am calling “The Great Purge of 2025,” I’ve been sorting things in my basement, in my bookcases, and my many dressers and closet with the goal of taking stock and lightening both figurative and literal loads. There are always three piles: keep, get rid of, throw away. I was forced into this position by our upcoming move, but what I’m finding is that the more I go through this process of reviewing and eliminating, the more I want to do it. The easier it becomes.

The psychic weight of all our stuff is a real thing, and just like most Americans, I’ve fallen into the trap of “more stuff = more happiness” my whole life. I’ve always felt like I “might need” that one thing I haven’t looked at for 20 years. Or like I’m ever going to want to read my teenage poetry again. Or what about those college papers on Shakespeare’s “The Merchant of Venice,” or on the looming, missing father figures in Baldwin’s literature. On sexuality as control in John Updike’s Rabbit series (specifically, “Rabbit is Rich”). Or even better, the irony of a paper I wrote about “The Great Gatsby,” where my thesis focuses on how Gatsby is obsessed with acquiring all the perfect, expensive things of new wealth — not because he cares about those things, but because those things (gorgeous mansion, pool, parties with the see-and-be-seen crowd that last until dawn, a walk-in closet with gorgeous clothing tailor-made for him) are a means to an end: if he has the things, he can catch Daisy’s attention. And if he can get her attention, then he can win back “the one who got away.” But we all know how that story ends, don’t we?

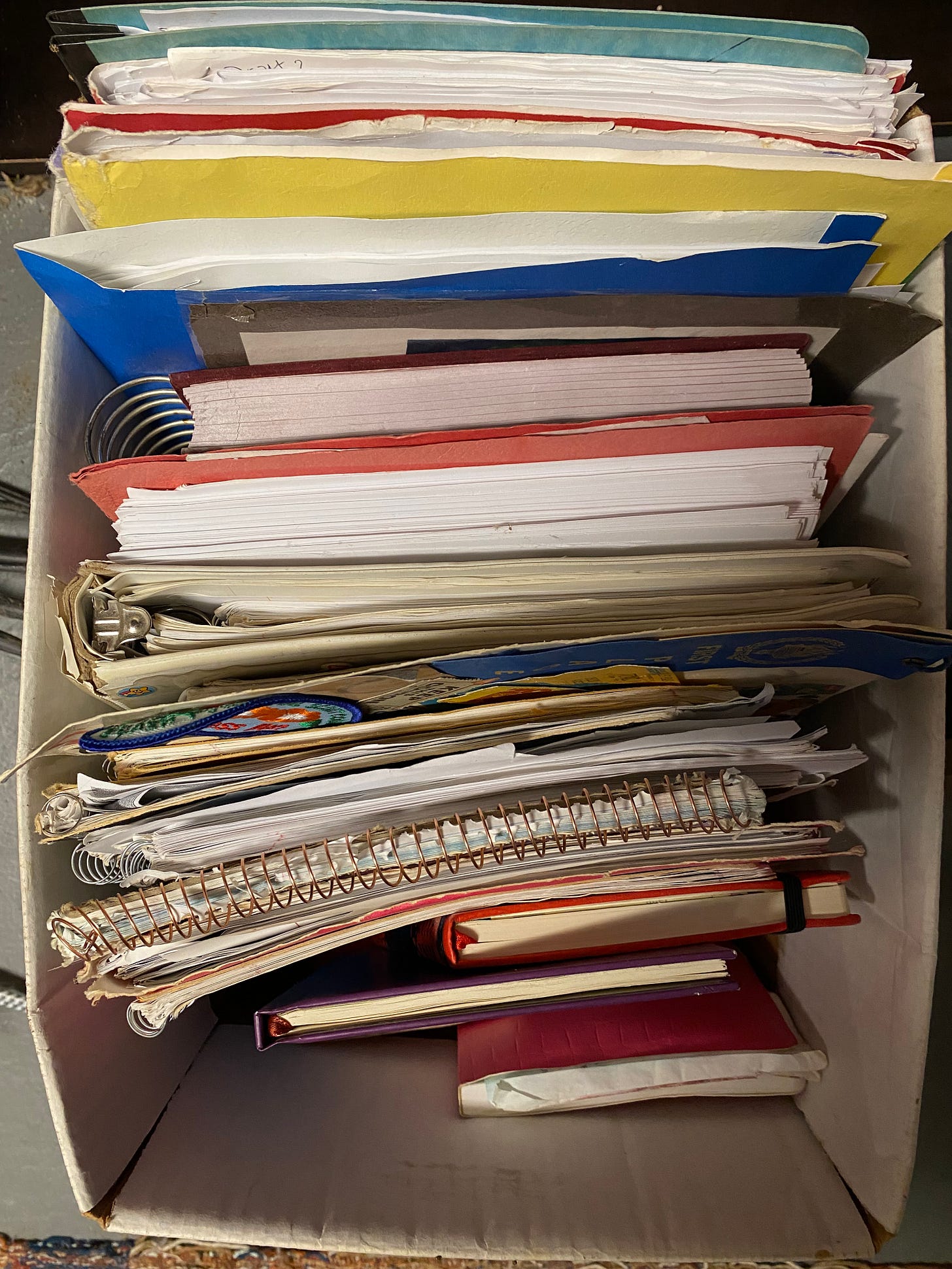

The sort-and-purge process has been beneficial in another way, too. While taking stock of the things I’ve amassed and carted from home to home, I am also becoming reacquainted with my old selves. For one, I am shocked at how much time I used to spend writing. Based on what I’ve found, I wrote on everything: in notebooks, on looseleaf in three-ring binders, on envelopes, on bill statements, on sticky notes. I wrote because I was compelled to, and I wasn’t worried about the output, or the finished product. I wrote for me, which is perhaps the best reason anyone could have for making things. I wasn’t worried about how it would stand up to critics, or whether it would be published in a literary journal. I just did it because I wanted to.

Which led me to think that, after many months of public writing hiatus, I should get back to it. After all, life is short and unpredictable — maybe you’ll like what I have to say, maybe you won’t, maybe you’ll end up somewhere in between. But what’s that matter?

A couple months ago, I was reading an excerpt of “The Creative Act: A Way of Being,” by Rick Rubin. This particular chapter, titled “The Abundant Mindset,” talks about letting material flow through you and out, so that it makes room for more creative material.

“A river of material flows through us. When we share our works and our ideas, they are replenished. If we block the flow by holding them all inside, the river cannot run and new ideas are slow to appear.”

— Rick Ruben, “The Creative Act: A Way of Being”

Letting go and releasing is a necessary part of creating more space, of setting the table, of inviting more in, whatever more looks like to you. I promised myself that this would be the year of remaining open. That I would listen more to the dynamics of myself, of the patterns of the season, of the universe’s nudging. That I would set aside my Type-A tendencies — even going as far as to say, “no resolutions, not this year” — to see where it took me. To be able to sit in the weirdness and just accept that it’s there, instead of trying to control every last thing.

As we start spring in earnest, with the wind blowing and the sun’s hours lengthening and the sprouts popping, I feel like this is exactly the right place to be. I look out my window and the wind is so forceful that I cannot tell what is a leaf and what is a bird. Everything blows past so quickly, and this gives me a pause of delight. I try to temper my (very normal) anxieties about moving with the concurrent reality that nature, too, is moving: it’s transitioning, life is opening up, things are being cleared out by wind and rain to make way for the new.

When my friend Amy and I talked a few weeks ago, I told her I had started the purge process. “It feels really good to be intentional about what you take with you,” she said. That stuck with me. I keep turning it over in my mind. It prompts a larger question for me, which is this: what kind of life do I want to live? What kind of space can I cultivate that is supportive of that? All of these things matter, and after all, we spend more time in our homes than most other places in our lives. It makes sense, then, that there’s a symbiotic relationship between the spaces we inhabit and the lives we live. I want to make sure it is a mutual relationship. I want to reflect my values, hopes, and passions in the space itself. That means I’ve been looking at things through the lens of, does this belong where I’m going?

In a similar way, when I stay in my teenage bedroom at the farm, I encounter the ephemera of a younger, different self. I suppose this kind of feeling is more pronounced if you truly leave a place. And when I’m in that bedroom, my adult self feels like a giant peering into a diorama frozen in time. I’ve peered into the closet to see what was still hanging there. I’ve looked at the jewelry, charms, and single earrings left in the trinket dish. The harmonica, the homemade cassette tape Andrew recorded of Nirvana’s “Nevermind,” the stuffed Boyd’s Bears I outgrew decades ago, but couldn’t bring myself to get rid of. Regardless, something happens in this interplay between past and present. It’s an alchemy of time.

On one intermittent break between packing and working and the daily detritus of life, I came across

. “Faded Red Tin,” an essay that unpacks the power of objects and the stories they hold, deeply resonated with me, a kid for whom stories were second nature. Stories were how I lived. I saw myself in young Dan as he rooted through the previous owner’s items in the attic. The focus on an object — in this case, a red tin that had once contained medicine to treat hemorrhoids — was at turns funny and dark, light and sad. The object becomes a meditative koan of sorts, a way to expand and collapse the story, a way to establish fact but also imagine a possible past, while acknowledging the unknown. And what’s more, Savage notes how haunted he is by story, by possibility. That’s exactly how I felt, going through boxes of items my father would buy at auction. I’d hold them and try and imagine who once owned them, what their lives were like. Where they were now. Whether they died peacefully, or whether, as in the case of Savage’s ghost, they had a more tragic end.I’m sure you weren’t expecting to get here. I wasn’t, either. But I love the idea of object as koan, as story, as possibility. As a way to revisit a previous self — and what’s more, a way to inform the future. To ask the question: who, and what, do I want to be? I don’t think we’re ever too old to ask.

As always, I love this! We have decided we really should move every 10 years as it forces us to part with stuff! Continue to purge , you will definitely feel better for it, and enjoy your new home!