Grief math: a different kind of logic

(Content warning: death, sibling loss. If it's too tough to read, it's okay to skip. I experimented & wrote this hybrid essay in a slightly different format.)

On May 17, 2025, it will have been 9 years since my brother Andrew died. Or at least, since his physical form as a human being — blood, bones, sinew, skin, beautiful heart, beautiful brain — has been gone from this planet. That’s 3,287 days, roughly speaking. It’s 78,888 hours, more than 4,700,000 minutes.

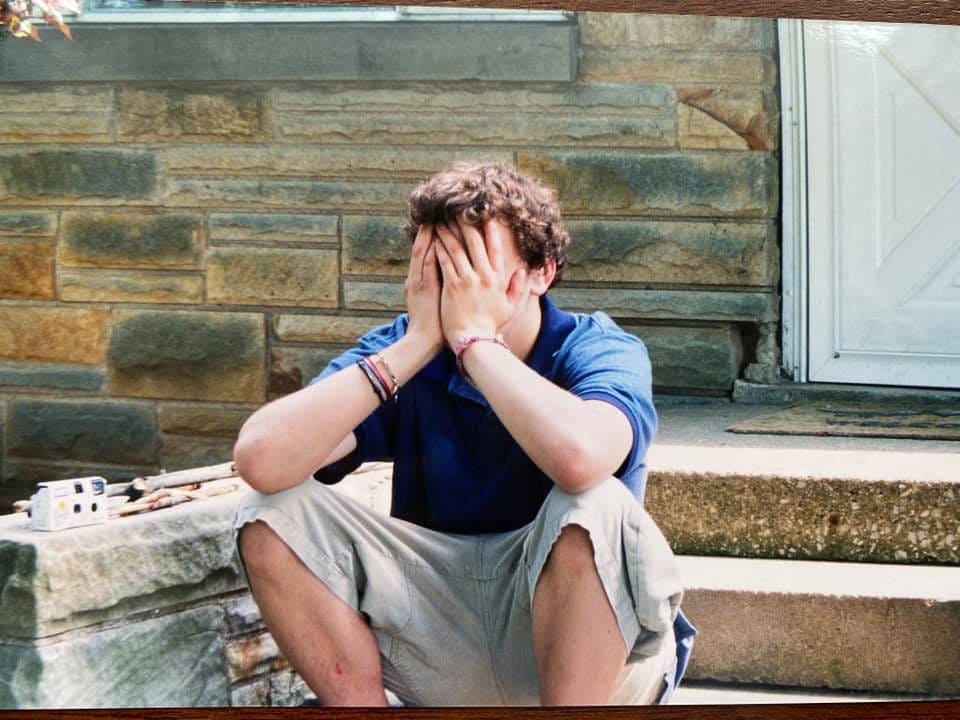

I do this math because it is a reminder of space and time in the after, a reminder how far I’ve come in a place where I didn’t know how I’d survive. It’s proof that I’m still here, living and breathing. Because there was a time grief rendered me dumb and mute. There was a pain cave I went to then. It was dark and it felt endless. Each mirror was a funhouse where my image would dissolve into his. I became afraid of myself. I was there in that cave, and I was terrified, and I didn’t think I would ever leave.

I don’t know how to quantify the energy expended by a human being when they die, or how it’s absorbed back into the universe. But if the laws of conservation of energy are to be believed, then death is not a destroyer, but a transformer: the energy becomes something else. I do not have the equation to solve for that, for what his energy became.

I’ve never been very good at math.

Every May, in the days leading up to his death anniversary, I play a game of chicken with the calendar. I erase the number. I check myself: do I know what date it is? I have forgotten, intentionally, the exact date of his death so that it does not bore into me like a freight train with no emergency break. I tiptoe around it. I think that if I misremember, if I lose track of the days, I will not have to face it. This is a trick I play on myself. It works until it does not. May, then, becomes a month of sadness that washes over me, in and out with varying severity, like the tide.

The 17th. The date is the 17th.

He was 27 when he died, three months short of his 28th birthday. One thing that was eerie to me was his fixation on “The 27 Club.” All his life, he was drawn to talented, troubled artists who died of tragic circumstances when they were 27 years old: Kurt Cobain, Janis Joplin, Amy Winehouse.

On the dresser in my teenage room, there’s a home-recorded cassette tape Andrew made of Nirvana’s “Nevermind,” the title scrawled on it in black Sharpie, and a smiley face with x’s for eyes.

In the days after Andrew’s death, I used journals as a way to mark time. To keep track of its passage, since I lost all ability to do so. I would think it was 8 and it would be 11. I would sleep and I would wake up and I would not know what day of the week it was, let alone what date it was. Some of the journal entries are marked with two days, since I was journaling late night into early morning.

I began making lists. Counting things. All attempts to make sense, to build a logic in a new world where none existed. I made a list of Andrew’s medications — 10 of them. I looked up dosages online. I made a list of what they were used to treat.

In his journals, Andrew made lists too.

“This is Me: My list of good personality traits” was an entry dated from February 28, 2016. Some quick math: that was less than 3 months before his death, 79 days to be exact (2016 was a leap year). Math is heavily reliant on logic.

In grief, my counting and pattern-making becomes its own way of assembling facts. I begin to apply mathematics — addition, subtraction, equation-making — as a way to make further sense, to extract a pattern, to create meaning where there is none. It is an imposition of control. It means nothing to an outsider, and yet it means everything to me.

In another journal, in the beginning of 2015, Andrew wrote: “27 is looming.”

He would turn 27 later that year. It would be his last birthday earthside.

Once I wrote, “I think of place as a reckoning in a way that time isn’t. Time is a kind of softness that creeps up on you, takes you by surprise. Place, on the other hand, is an immediate assault on the tangible. Place is not so forgiving. Here’s an equation: place + time = loss.”

Some math equations are unsolvable. Such equations are called “inconsistent,” “open,” “conjectures.”

A conjecture, in math and otherwise, is “an opinion or conclusion formed on the basis of incomplete information.”

A list of grief conjectures, unsolvable problems, questions with no provable answers:

The number of times I meant to call or text Andrew, only to remember I couldn’t

The weight of Andrew’s boxed cremains as I held them in my lap, wrapped in a yellow plastic bag that stuck to my skin

The way time moves in grief — fast, slow, forward, backward, all at once

The decibels produced as I wailed in my bathtub, curled up in a ball, after hearing of Andrew’s death

The many ways in which I have described having a dead brother to the world — to lessen my suffering, to lessen their suffering, to avoid having to explain altogether

The number of times I have returned to the pain cave

The number of times I will write around the space of loss, the question of grief, the constant presence of love: infinite, unquantifiable.

Ever-expanding, like the universe, until I too become a transmutable equation: my human body rendered into heat energy, atoms and star stuff scattered into the universe.

I understand.

I knew Andrew—he was incredibly kind and so smart. I'm truly sorry you're carrying this loss, Ashley. I can’t imagine how hard it’s been, but your words are powerful, and I’m grateful you’re sharing them.