A ghost in the machine

What can AI teach us about ourselves? A mixed bag on memory, grief, running, and a haunting (CW: body dysmorphia, sibling loss)

If you’re expecting me to answer that question, let me stop you right here. I’m not a neuroscientist, coder, or AI expert. But I am a writer, and I’m inherently curious, even about things that I have made a Herculean effort to avoid learning about up until now (ahem, AI). And as a curious writer of essays, I like to chew on big, unanswerable questions because I feel like there’s a lot to gain from exploration.

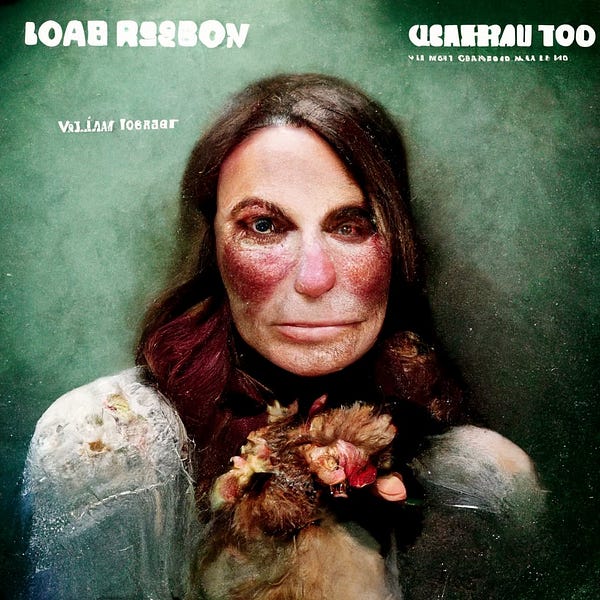

First, some honesty: I’ve felt a strong sense of rejection toward AI, and toward understanding it, even though it’s used in all kinds of technology applications throughout the world. I feel like we’ve all seen enough shows and movies where AI ultimately gets the upper hand, decides humans are sort of useless, and wipes them out. But recently, I came across a story that completely sucked me in. It’s a story about an AI-generated woman named “Loab,” who’s being called the “first AI cryptid” and a “latent space haint,” and how she came to be. And honestly, it’s kind of a wild ride. The user who created Loab, known as Supercomposite, wrote a Twitter thread about how she was created, along with some explanations about what could be happening. (FWIW, I think another fascinating part of this is that even AI experts can’t completely explain it.)

The concept of “latent space” is the space between the input (the command) and the output (the end result) — so essentially, the place with all the data where the AI tool is searching. Loab is not a person, but her likeness has now been imprinted multiple times over by an AI “mind.” What’s fascinating about her is that she continues to show up, even when her creator experimented to try and erase or remove her from the results. In the creator’s words, the AI is behaving unpredictably, despite many tests and experiments. That’s curious because it means the “why” is unknown. And that means there’s much about AI we don’t know, despite thinking we do.

A quick thought experiment: ask yourself how you feel about AI. Do you get excited? Irritated? Repulsed? Full of doom? Then, try thinking of what you do know about AI — where and how it’s used in everyday life. Chances are, most of you have more feelings than you do knowledge, and that knowledge is likely based on headlines around how AI has been used for bad, or the copyright- and privacy-infringing discourse (all valid conversations).

Making assumptions is a deeply human thing — we often have biased thoughts about how much we actually now, and really, our own brains are programmed to fill in the gaps, make inferences and leaps of logic. The reality is that we think we’re smarter than we actually are, and often think we have a better understanding of things than we actually do. (This cognitive bias is called the Dunning-Kruger effect, if you were wondering, and seems to be exacerbated by technology and our access to information.)

When it comes to AI, I’m full of conflicting feelings that run the gamut of eye-rolling, intrigue, anxiety, and even a little fear. I want to be dismissive because part of me doesn’t want the change that it brings, or because I don’t know what kind of change it will bring. I’m also reluctant because I don’t understand it well at all.

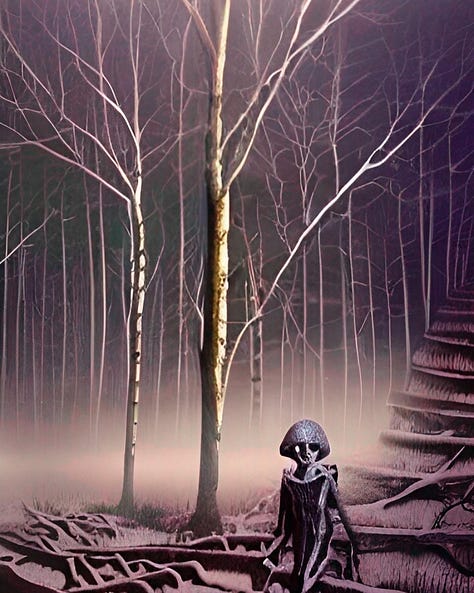

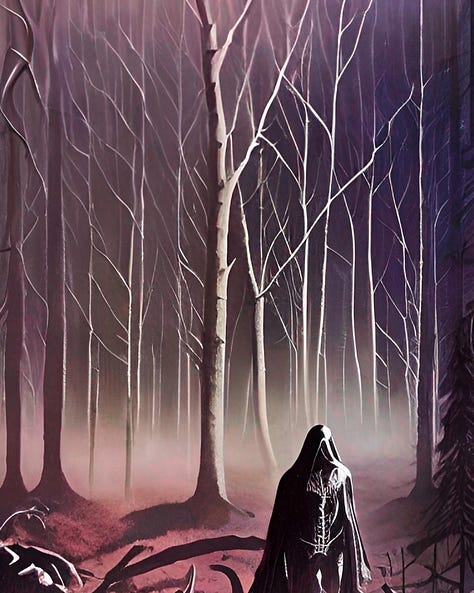

Below are AI art images I created by entering a series of prompts and constraints into the Dream app. All were created from the same input, I just spawned dozens of variations of them. I was curious about the concept of haunting as it pertained to machine-created entities.

Etymology tells us the word “haunt” (late 13th century) means “frequently” or “to frequent.” If you go back further to the 12th century, haunt’s meaning derived from Old Norse “heimta,” or “to bring home.” To haunt is to bring, to carry. I wonder what that means in latent space — the place where the AI input searches for data and creates an output.

I wonder what that means for memory — the place where the meaning of inputs shift over time, creating variations and replications of themselves, a different part called forth depending on the constraints, on what’s emphasized or de-emphasized, on what’s determined important or worth forgetting, what’s included and what’s left out.

When I went to my parents’ farm for Thanksgiving, it was a different sort of homecoming. I went with the intention that I would change the pattern, that I would bring new energy to the situation. We all get into habits, and I do, too — with some things, I’ve settled into what felt like a predetermined way of being — lower energy, resignation of some of my agency, a tendency to go with the flow of things. This time I wanted to try something new.

On Thanksgiving morning, I took a 25-minute run around the farm. Past the spiky, shorn fields, dodging branches, alongside the pond. There was the sweet smell of wild onion in the air. Milkweed pods had dried and burst, their white filigree seeds rustling in the wind. The pound of blood in my ears, punch of air in my lungs. I was grateful for this body and how I have recommitted to it, to caring for it, to loving it, even when it’s hard.

It felt like hardwiring a new memory, a new association, even though I had moments where I felt visited by my former self. The self who, after high school cross-country practice, would come home and run extra miles around my backyard fields. I wasn’t motivated by greatness or getting better, but rather, making my body light and concave. I contrasted the girl then with who I am now in the moment. How now, running was difficult and hard, but it felt like a way of taking care of myself, a way to access something new in myself. To continue cultivating a sense of mental strength. How I relished the moment so much because wow! I was out here breathing hard, legs moving, blood pumping. I was alive, and my body is capable, and before this day, I didn’t know it was capable of this. What a joy to discover that!

In the farmhouse kitchen, there’s an antique chalkboard hanging on the wall. On it is a chalk-scribbled Christmas tree with bulbous ornaments and “MERRY CHRISTMAS!” scrawled across the top. I’ve written about this before, in many different contexts. It’s my sibling A.’s handiwork, something they wrote the last Christmas before they died. It was the last family gathering I can remember having with A. and my mother. It was one of the last times I remember seeing A., their hand moving across the chalkboard, tattooed knuckles and ringed fingers gripping the chalk. I vaguely remember playing Scrabble before returning A. to their apartment in Sandusky, wishing they’d stay, but they never did anymore.

The memories have been processed, filtered, reprocessed, re-filtered. Critical portions of it have been lost, de-prioritized. Forgotten.

Which leads me to the question: how did I end up here? I do this so often, starting from one point with open space before me, only to end up circling my own grief. I retrace my steps, with endless variations. Like Loab, it’s an apparition that keeps appearing in latent space, encoded and repeated in the tissues of my own brain. My grief is a haunt, my haunt. I carry it with me wherever I go.

You make me think when I read your essays and I love that! I always enjoy what you say, sometimes I read your essays 3 or 4 times so I’m sure I have it! Your grief is still raw Ashley, I’m not sure you ever come to grips with it, and maybe that’s not a bad thing. You will over time find a place for it……..and you will continue on, just in a different mindset. Continue to write , Ashley, as you reach the very bottom of my soul every time I read your words. I’m so proud of you!

So very lovely, Ashley.